The patient is a 12-year-old Arabian gelding used for endurance riding. The clinic was called as the horse was not eating well and started to show signs of abdominal discomfort, such as stretching out and acting like he had to urinate, without actually urinating. Upon physical examination, Dr. Crawford determined that the horse was indeed suffering from a very mild bout of colic, but no clear reason was evident at this time.

Since the signs of colic were mild and intermittent, a gastroscope was scheduled. Gastroscopy involves sending a thin fiber optic camera through the nasal passages into the stomach to visualize the lining of the stomach and beginning of the small intestine.

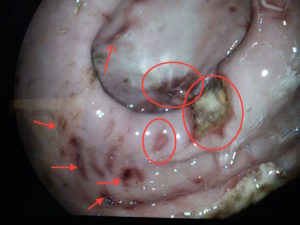

Gastroscopy revealed severe gastric ulcers (erosions of the normal tissue) in both the upper and lower parts of the stomach.

Gastric ulcers have been estimated to be present in 60-90% of adult horses, depending on age and job. Ulcers are also found in 25-50% of foals. In order to understand ulcers, a basic understanding of equine anatomy and physiology is warranted.

The horse stomach is divided into two distinct regions, the esophageal (non-glandular) region and the glandular region. The esophageal region, or squamous mucosa, covers approximately one-third of the equine stomach and has no glands or secretions. The glandular region covers the remaining two-thirds of the stomach and contains glands that secrete hydrochloric acid, pepsin, bicarbonate, and mucus. The two regions are separated by a very distinct line called the margo plicatus.

The equine stomach continuously secretes variable amounts of hydrochloric acid throughout the day, and secretion of acid occurs without the presence of feed material. Horses are designed to be grazers, therefore always having something in their stomach to help buffer the acid. The stomach secretes approximately 1.5 liters of gastric juice hourly, so if the stomach is empty of feed material the acid is just sitting there. In horses that perform to maximum exertion, ulcers can be more common due to the high abdominal pressure noted with exercise. Horses that are fed large amounts of grain or large meals, as opposed to grazing or diets that are primarily based in forage are also at higher risk of ulcers.

Clinical signs of gastric in horses can include poor appetite/failure to finish a meal, dullness, attitude changes, decreased performance, reluctance to train, poor body condition, rough hair coat, weight loss, and low-grade colic.

Gastroscopy is the only way to definitively diagnose gastric ulcers. Treatment includes dietary and lifestyle management, such as increased turn out and forage consumption, and decreased training in certain horses for a period of time. Medical treatment involves inhibiting gastric acid secretion, which is done with an FDA approved drug called Gastrogard.

Prevention of ulcers is key. Limiting stressful situations, frequent feedings and free-choice access to grass or hay is imperative. This provides a constant supply of feed to neutralize the acid and stimulate saliva production. If you have any questions about ulcers or your horse, please give us a call.